German Lutheran church now serves growing Asian community

Vanessa Hua, San Francisco Chronicle Staff Writer

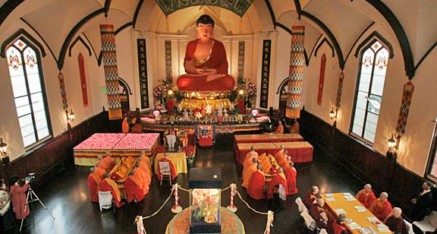

Practitioners engage in ceremonies at the new temple in the above photo. On Sunday, those who died in the tsunami will be blessed in a service.

Inside an old German Lutheran church in San Francisco, Chinese nuns sit on the glossy wooden floors, wearing headphones, listening to Buddhist mantras on portable CD players.

Gone are the pews and the church piano, but the organ pipes and stained glass windows remain — a backdrop to giant Buddha statues at the Hua Zang Si temple, which opened its doors this week in the Mission District. The Buddhist temple reflects the changing demographics of this working- class Latino neighborhood, and of the Bay Area.

“As the Asian immigrant population becomes more diverse and complex and comes into money, they want to do things that acknowledge and empower their heritage,” said John Nelson, an associate professor of religious studies at the University of San Francisco. “Temples are community centers, where people go to affirm their identity.”

On Dec. 26, Hua Zang Si began three days of ceremony to celebrate its opening and the birthday of Amitabha Buddha, one of the many Buddhas, who is believed to reside in the land of ultimate bliss. This Sunday, the temple will hold a ceremony starting at 10 a.m. to bless those who died as a result of the quake-caused tsunami in southern Asia.

Built in the 1900s, the structure originally housed St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Many in the immigrant German congregation likely worked at the nearby tanneries and breweries along Precita Creek, historians say. Located on 22nd Street, the church was just out of reach of the fire that razed much of the city following the 1906 earthquake.

After World War II, German, Italian and Irish families began moving from the Mission to the west side of San Francisco and out of the city. In 1992, the congregation voted to serve the neighborhood’s growing Latino population, moving to a new church around the corner and renaming itself St. Mary and St. Martha Lutheran.

The old church became a private residence and was to be divided into condominiums, until the United International World Buddhism Association purchased it and the adjoining parish residence for $2.5 million in 2002, according to public records. And so the temple was born, with a new set of red doors with traditional Chinese lion-headed knockers, Chinese signs and a Buddha in the lobby.

About two dozen nuns live at the temple compound. Each day, they rise around 5 a.m., and do not go to bed until midnight — meditating, praying and studying Buddhist teachings. The nuns watch television to get a better sense of what Americans are like, they say.

The nuns, in yellow and grey robes, venture out in the bustling neighborhood to buy groceries and supplies. The temple is down the street from Castillo Express, Elon’s Beauty Salon and Panchita’s, which serves South American food.

“We’re like other people. We have to eat, too,” Cheng Hsueh Shih said in Mandarin. The rosy-cheeked nun with a shaved head had hip rimless glasses and wooden prayer beads on her wrist. A vegetarian, she has tried the Mission’s famous burritos, but says she prefers Chinese food.

On a recent weekday, passers-by stopped and pointed at the temple, marveling at the Maitreya bodhisattva, or godlike being, visible behind the lobby’s glass doors. Chubby and smiling, he is a future Buddha, and is believed to currently reside in heaven.

“It’s great that it’s still being used for spiritual worship,” said Max Kirkeberg, a professor of geography at San Francisco State University who has chronicled changes to the city’s landscape for decades.

The temple bases its teachings on those of Shakyamuni Buddha, who lived about 2,500 years ago in what is now Nepal. It has not adopted the viewpoint of any particular sect and wants to attract a broad range of followers. Smaller branches of the temple are in San Jose and Sanger (Fresno County). Hua Zang Si joins more than a dozen Buddhist institutions in San Francisco, including the Sokoji-Soto Zen temple in Japantown and the Rigpa Center in the South of Market.

On the first floor of the temple, in the Precious Hall of the Great Heroes, a statute of Shakyamuni Buddha dominates. Skanda bodhisattva, a general clad in armor with a sword, stands to his right, protecting the temple from evil.

The temple’s giant Buddhas were constructed in Taiwan, divided into pieces and reassembled inside by artisans. Before the Buddhas sit offerings of coffee, grapefruit, apples, boxes of raisins, cans of Coca-Cola, incense and artwork.

Dong Ai-Yuan, a disciple visiting from Fresno, said she became a Buddhist about 15 years ago. The religion helps bring her peace and good luck, and keeps her family safe, she said, adding that she has no fear of the future because she knows what her fate holds.

On the second floor, a 21-foot-tall Amitabha Buddha, draped in a red robe, fills one end of the room. Before him, a thousand cups of water, changed daily, serve as an offering to Buddha. Nearby is a ceremonial wooden drum shaped like a fish. To learn as much as they can, the devoted must never rest and never close their eyes — like a fish.

The backyard — a city oasis in the shadow of surrounding Victorians — is home to a magnolia tree, which the faithful say rained nectar for three days, along with a miraculous lotus tub used in the bathing of the Buddha dharma, or teachings. In front, the building’s cornerstone carries an inscription in German referring to a New Testament text about the house of God, built upon the foundation of apostles, prophets and Jesus Christ. Now, beside the cornerstone, in gold Chinese characters on black background, a sign reads: This temple will teach you how to become a better person.

DEC

2004